LoRA

LoRa was introduced in the paper “LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models” by researchers from Microsoft in June-2021.

When Transformers were first introduced, researchers found success in transfer learning by taking pre-trained models (such as BERT, T5, etc.) and fine-tuning them on each downstream specific tasks. However, this means that for each downstream task, we learn a different set of parameters, thus needing to store and deploy many independent instances of these fine-tuned models. This becomes increasingly challenging (and infeasible) as language models become larger in size.

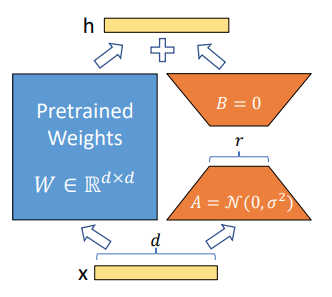

LoRA addresses this by representing weight updates with two smaller matrices (“A” and “B” in the figure below). The original weight matrix remains frozen and does not receive weight adjustments. Henceforth, we will use “LoRA modules” to refer to these smaller decomposable weight matrices that LoRA introduces.

- Fine-tuning is more efficient in terms of speed and memory consumption, since the number of trainable parameters is drastically reduced.

- Storage requirement is drastically reduced, since we only need to store the much smaller decomposed weight matrices.

- You can fine-tune multiple lightweight LoRA modules for different downstream tasks. At the beginning of inference, you load your base model. Then you can efficiently swap in and out different LoRA modules, based on the particular downstream task requirements.

- In the LoRA paper, the authors demonstrate that the performance of models fine-tuned using LoRA is comparable to the performance of fully fine-tuned models.

- Finally, LoRA does not add any inference latency because adapter weights can be merged with the base model. This is unlike previous adapters approaches (Houlshy et. al. 2019) that introduced additional adapter layers per Transformer block, which adds to the number of sequential decoding steps.

The LoRA Method

Specifically, the fine-tuning weight update is now defined as $W_{0} + \bigtriangleup W = W_{0} + BA$:

- $W_{0} \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times k}$ is the pre-trained weight matrix

- $B \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times r}, A \in \mathbb{R}^{r \times k}$ are the weight matrices that LoRA introduces, where $r \ll \text{min}(d,k)$

- $W_{0}$ is frozen, while $A$ and $B$ contain trainable parameters.

- For an input $x$, the forward pass is modified to: $h = W_{0}x + BAx$

Note that the above does not introduce any additional inference latency. This is because both $W_{0}$ and $BA$ are in $\mathbb{R}^{d \times k}$, which allows us to directly compute and store $W = W_{0} + BA$. When there is a need to switch to a different downstream task (with a different LoRA module $B’A’$), we can recover $W_{0}$ by subtracting $BA$ and then adding in $B’A’$

Empirical Experiments from the Paper

Using RoBERTa and DeBERTa as base models to evaluate on the GLUE benchmark dataset, the authors evaluated the LoRA method against: fine-tune the entire base model, adapter-tuning (inserting additional adapter layers in each Transformer block), etc. The authors applied LoRA towards adapting the $W_q$ and $W_v$ self-attention weight matrices.

- LoRA achieves comparable or better performance results on GLUE vs fine-tuning the entire base model. In contrast, adapter-tuning results in lower performance vs fine-tuning.

- Applying LoRA to ($W_q, W_k$) or individually towards $W_q, W_k, W_v, W_o$ result in lower results.

- Using $r=4$ or $r=8$ achieves good results.